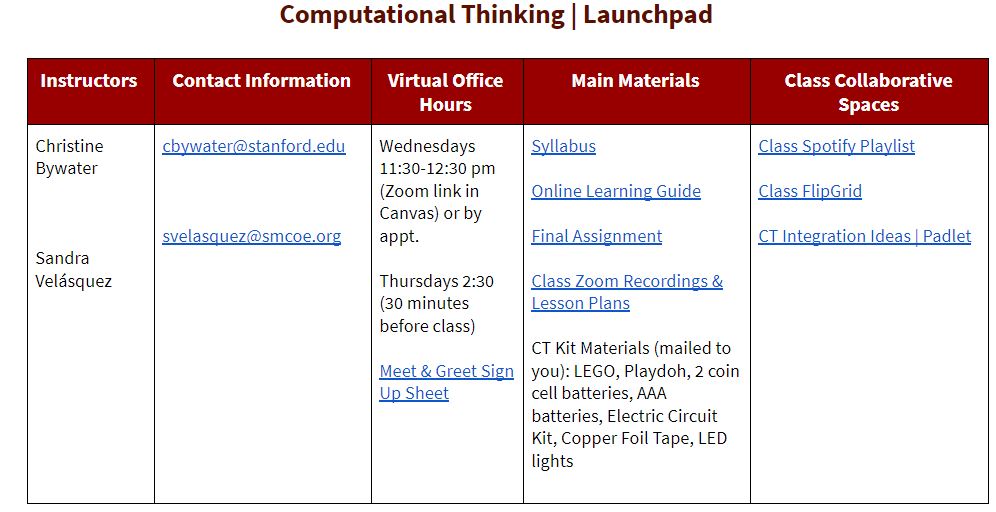

Christine Bywater is a Professional Development Associate for CSET in history, social science education, and educational technology. Her work centers on supporting the infusion of technologies and research-based pedagogy to ensure that instructional practices are anchored in the learning needs and interests of all students.

Sandra Velásquez is the Innovative Learning & Technology Integration Coordinator for the STEAM Center at the San Mateo County Office of Education. She supports SMCOE’s Making Spaces Regional Hub and the development of sustainable active learning spaces. In addition, she collaborates with CSET as a co-facilitator for computational thinking courses for pre-service and in-service teachers.

What has been your thinking around adapting your course to an online setting?

Velásquez: You’re going to get less engagement if you just continue to do what you were doing in- person. You can’t just plug in what you did before and expect the same results. We’ve taught the course before, so we already had our syllabus fully fleshed out, but we still spend a good four to six hours a week planning because we have to think about the course through a new lens. Retooling the course has taken a lot of time and effort. Our mindset is: “Yes, we’ve already taught the course, but how is it going to work in this online space?”

You can’t just plug in what you did before and expect the same results.

To help us decide what elements of the in-person course to try and keep, and which to let go, we keep going back to what good teaching is. What is our essential question, and what are the learning goals for each class? For whatever we throw out, and for whatever we have left, we always ask the question “How do we know that they learned what we intended for them to learn?” This forces us to go back to our learning goals and our essential questions. The technologies we’re using to bring the course online are not guiding our practice. The content is always still guiding our practice.

The technologies we’re using to bring the course online are not guiding our practice. The content is always still guiding our practice.

How do you decide what to include and what to exclude when adapting your course?

Bywater: The things I want to hang onto remotely are the experiences that created and supported the classroom culture; things that we do that help students feel seen and heard.

Velasquez: For example, we used to do walk-and-talks, where students would reflect on a question while walking through Stanford’s campus. So we asked ourselves, “Okay, how do we do a walk and talk virtually?” Well, we know that they all have iPads. So, during the break we asked students to start their iPads, we assigned partners, and asked them to get online do a remote walk-and-talk with their partners to reflect on a question. And they appreciated that! The feedback from participants was along the lines of “Oh, we didn’t realize how nice it would be to turn our screen off and talk to somebody on the phone and still walk around.”

What is missing from the online experience, and how have you managed to compensate?

Bywater: One thing that I’ve noticed we miss in the remote experience is the ability to listen in to students’ conversations as you would in person. You can’t really float in breakout rooms as easily as you can in person, so it’s harder to pick up on students’ ideas and push them further or redirect them if they’re a little off track.

You can’t really float in breakout rooms as easily as you can in person, so it’s harder to pick up on students’ ideas and push them further or redirect them if they’re a little off track.

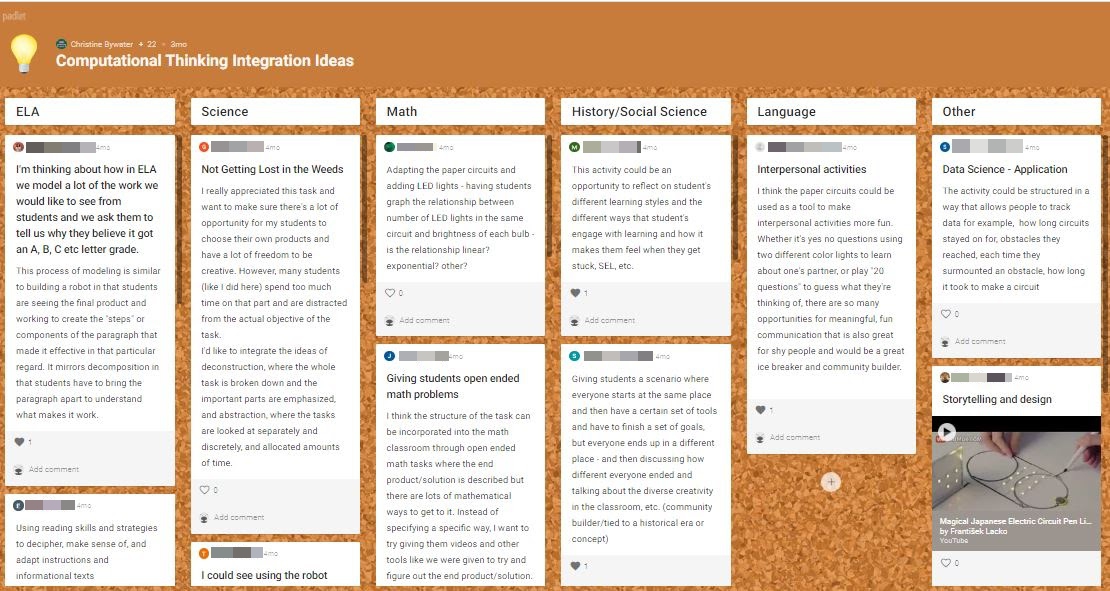

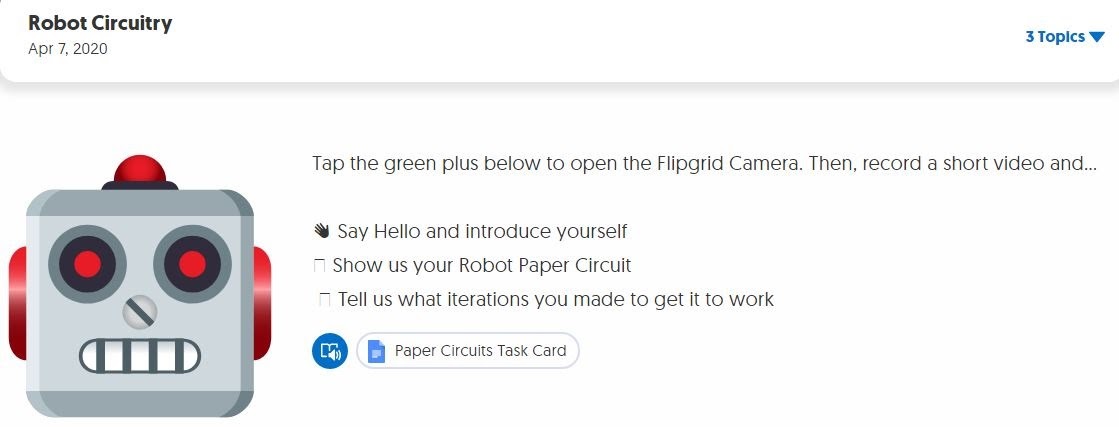

To compensate we’ve tried something that we’ve never done in person, which is the addition of reflection and video journals. These have really elevated the remote experience. After each class, students have an asynchronous activity they do and record in a Flipgrid. We also pose questions about the readings and activities for them to reflect on in a digital journal. Their responses give us a window into their thinking, so we can tell if they’re making sense of the ideas. These also provide a way for us to connect with the students in between class meetings.

Have you found any benefits to teaching online?

Velásquez: In our course, we ask students to tinker and build with technologies and tools that they may not be familiar with. For example, working with circuits and electricity. These sorts of things can make some people feel vulnerable. We mailed students packages of materials prior to the start of class so we could create experiences where they tinker and create.

We mailed students packages of materials prior to the start of class so we could create experiences where they tinker and create.

What we noticed in class—in person—is that many folks hide behind that fear and don’t fully engage in taking risks with some of the challenges that we present. Now, because of the move to online learning, students work on these projects offline, instead of in the classroom. An unexpected benefit of this is that it gives them more time to tinker in a safe space where they can actually push through the fear and some of those insecurities. The things they’ve produced have blown us away. We were just like, “Whoa, we didn’t expect them to engage in the content like this!”

One of the challenges of online teaching is ensuring everyone is comfortable with technology. Do you have a strategy for introducing your students to new tools?

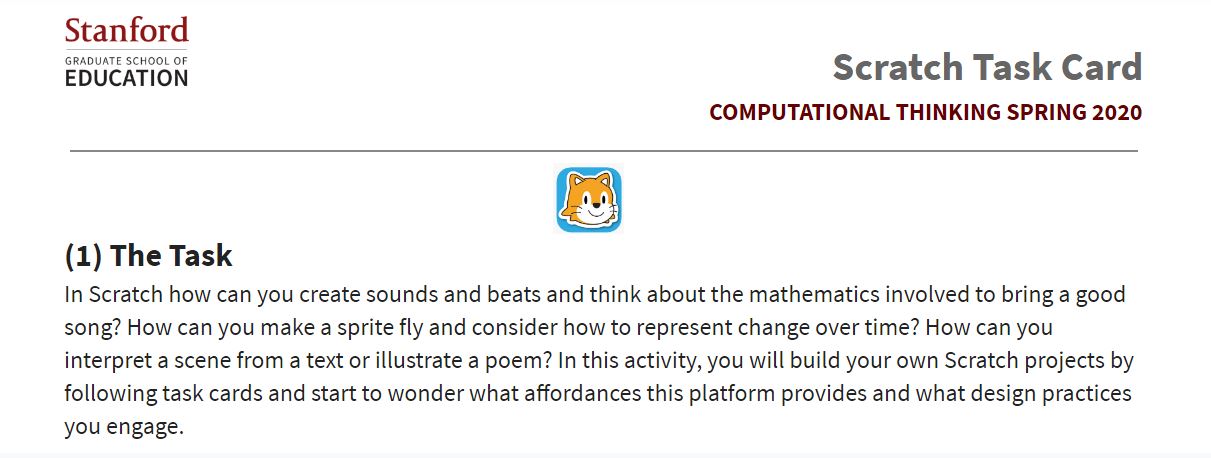

Bywater: I think we have a pretty good recipe for introducing students to new tools, tools like Scratch and Tinkercad, and things like that. Our recipe is we give them a task card. The task cards are all structured similarly. The task cards are all structured similarly. First, we ask them to spend a short amount of time discovering. Second, we link to YouTube videos, and maybe a little brief reading about how the tool works. Third, we give them some brainstorming around the task we want them to do. Finally, we introduce their task.

We intentionally do not teach the tool step-by-step. We don’t think that’s how it should be done in classrooms. One of the mindsets we want the students to walk away with, not only in computational thinking, but as teachers, is that it’s okay to try things out and fail. “If you were working with a new tool and tried to do something that didn’t work, what could you do differently? How could you ask your peers for help?”

One of the mindsets we want the students to walk away with, not only in computational thinking, but as teachers, is that it’s okay to try things out and fail.